Now

one

big

question

I

have

about

the

index

is

how

it

is

calculated.

And

this

how

the

Economist

Intelligence

Unit

explains

it

from

their

free

report

you

can

download

here

(note

has

loads

of

good

findings

beyond

the

raw

scores

above).

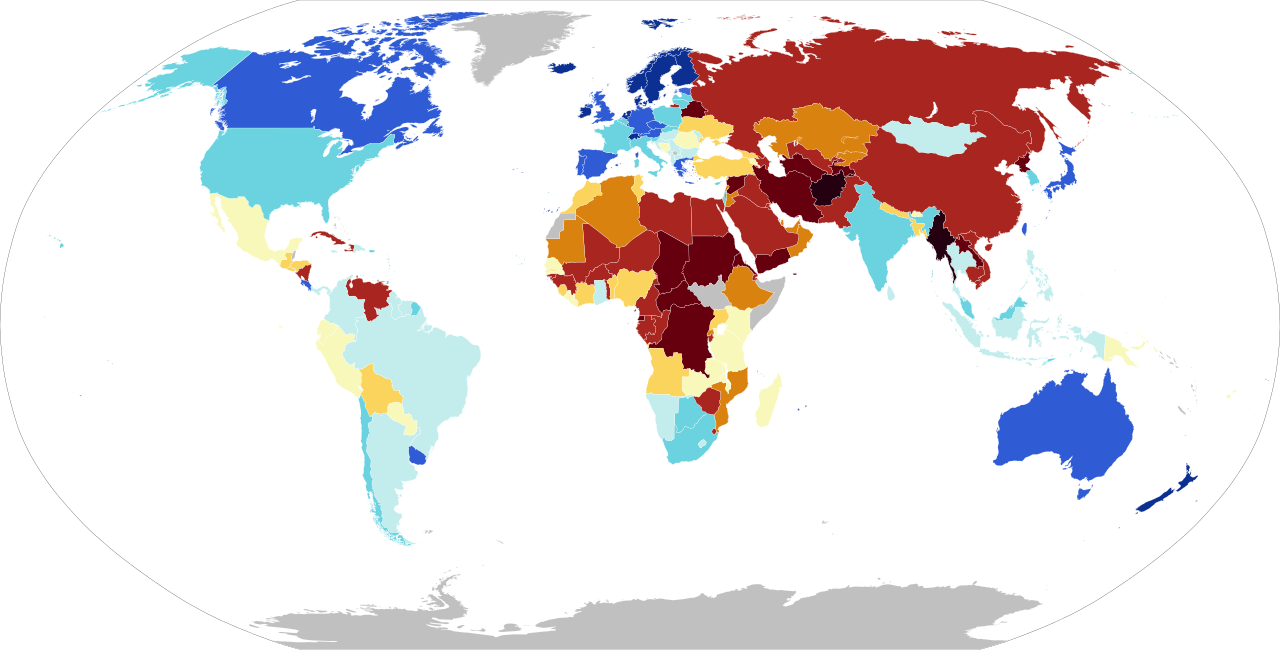

Methodology

The

Economist

Intelligence

Unit’s

index

of

democracy,

on

a

0

to

10

scale,

is

based

on

the

ratings

for

60

indicators,

grouped

into

five

categories:

-

electoral

process

and

pluralism; -

civil

liberties; -

the

functioning

of

government; -

political

participation;

and -

political

culture.

Each

category

has

a

rating

on

a

0

to

10

scale,

and

the

overall

Index

is

the

simple

average

of

the

five

category

indexes.

The

category

indexes

are

based

on

the

sum

of

the

indicator

scores

in

the

category,

converted

to

a

0

to

10

scale.

Adjustments

to

the

category

scores

are

made

if

countries

do

not

score

a

1

in

the

following

critical

areas

for

democracy:

-

Whether

national

elections

are

free

and

fair. -

The

security

of

voters. -

The

influence

of

foreign

powers

on

government. -

The

capability

of

the

civil

service

to

implement

policies.

If

the

scores

for

the

first

three

questions

are

0

(or

0.5),

one

point

(0.5

point)

is

deducted

from

the

index

in

the

relevant

category

(either

the

electoral

process

and

pluralism

or

the

functioning

of

government).

If

the

score

for

4

is

0,

one

point

is

deducted

from

the

functioning

of

government

category

index.

The

index

values

are

used

to

place

countries

within

one

of

four

types

of

regime:

-

Full

democracies:

scores

greater

than

8 -

Flawed

democracies:

scores

greater

than

6,

and

less

than

8 -

Hybrid

regimes:

scores

greater

than

4,

and

less

than

6 -

Authoritarian

regimes:

scores

less

than

4

Full

democracies:

Countries

in

which

not

only

basic

political

freedoms

and

civil

liberties

are

respected,

but

which

also

tend

to

be

underpinned

by

a

political

culture

conducive

to

the

flourishing

of

democracy.

The

functioning

of

government

is

satisfactory.

Media

are

independent

and

diverse.

There

is

an

effective

system

of

checks

and

balances.

The

judiciary

is

independent

and

judicial

decisions

are

enforced.

There

are

only

limited

problems

in

the

functioning

of

democracies.

Flawed

democracies:

These

countries

also

have

free

and

fair

elections

and,

even

if

there

are

problems

(such

as

infringements

on

media

freedom),

basic

civil

liberties

are

respected.

However,

there

are

significant

weaknesses

in

other

aspects

of

democracy,

including

problems

in

governance,

an

underdeveloped

political

culture

and

low

levels

of

political

participation.

Hybrid

regimes:

Elections

have

substantial

irregularities

that

often

prevent

them

from

being

both

free

and

fair.

Government

pressure

on

opposition

parties

and

candidates

may

be

common.

Serious

weaknesses

are

more

prevalent

than

in

flawed

democracies—in

political

culture,

functioning

of

government

and

political

participation.

Corruption

tends

to

be

widespread

and

the

rule

of

law

is

weak.

Civil

society

is

weak.

Typically,

there

is

harassment

of

and

pressure

on

journalists,

and

the

judiciary

is

not

independent.

Authoritarian

regimes:

In

these

states,

state

political

pluralism

is

absent

or

heavily

circumscribed.

Many

countries

in

this

category

are

outright

dictatorships.

Some

formal

institutions

of

democracy

may

exist,

but

these

have

little

substance.

Elections,

if

they

do

occur,

are

not

free

and

fair.

There

is

disregard

for

abuses

and

infringements

of

civil

liberties.

Media

are

typically

state-owned

or

controlled

by

groups

connected

to

the

ruling

regime.

There

is

repression

of

criticism

of

the

government

and

pervasive

censorship.

There

is

no

independent

judiciary.

The

scoring

system

We

use

a

combination

of

a

dichotomous

and

a

three-point

scoring

system

for

the

60

indicators.

A

dichotomous

1-0

scoring

system

(1

for

a

yes

and

0

for

a

no

answer)

is

not

without

problems,

but

it

has

several

distinct

advantages

over

more

refined

scoring

scales

(such

as

the

often-used

1-5

or

1-7).

For

many

indicators,

the

possibility

of

a

0.5

score

is

introduced,

to

capture

“grey

areas”,

where

a

simple

yes

(1)

or

no

(0)

is

problematic,

with

guidelines

as

to

when

that

should

be

used.

Consequently,

for

many

indicators

there

is

a

three-point

scoring

system,

which

represents

a

compromise

between

simple

dichotomous

scoring

and

the

use

of

finer

scales.

The

problems

of

1-5

or

1-7

scoring

scales

are

numerous.

For

most

indicators

under

such

systems,

it

is

extremely

difficult

to

define

meaningful

and

comparable

criteria

or

guidelines

for

each

score.

This

can

lead

to

arbitrary,

spurious

and

non-comparable

scorings.

For

example,

a

score

of

2

for

one

country

may

be

scored

a

3

in

another,

and

so

on.

Alternatively,

one

expert

might

score

an

indicator

for

a

particular

country

in

a

different

way

to

another

expert.

This

contravenes

a

basic

principle

of

measurement,

that

of

so-called

reliability—the

degree

to

which

a

measurement

procedure

produces

the

same

measurements

every

time,

regardless

of

who

is

performing

it.

Two-

and

three-point

systems

do

not

guarantee

reliability,

but

make

it

more

likely.

Second,

comparability

between

indicator

scores

and

aggregation

into

a

multi-dimensional

index

appears

more

valid

with

a

two-

or

three-point

scale

for

each

indicator

(the

dimensions

being

aggregated

are

similar

across

indicators).

By

contrast,

with

a

1-5

system,

the

scores

are

more

likely

to

mean

different

things

across

the

indicators

(for

example,

a

2

for

one

indicator

may

be

more

comparable

to

a

3

or

4

for

another

indicator).

The

problems

of

a

1-5

or

1-7

system

are

magnified

when

attempting

to

extend

the

index

to

many

regions

and

countries.

Go to Source

Author: Brilliant Maps